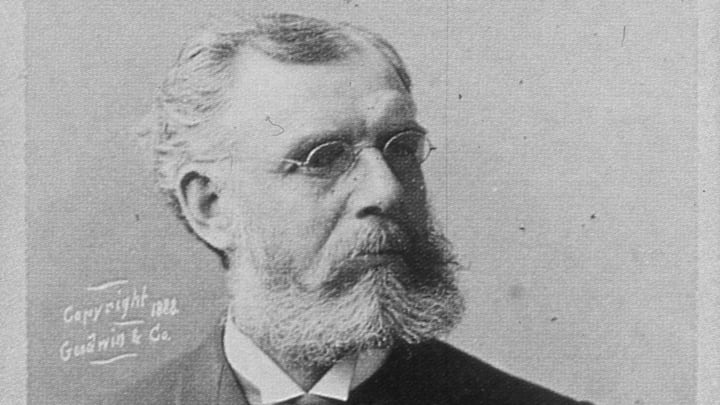

The Atlanta Braves franchise began life as the Boston Red Stockings in 1871. The club survived while others failed because of the man who built, played for, and managed it, Harry Wright.

The first manager in the history of the Atlanta Braves Franchise, William Henry “Harry” Wright, was called the father of professional baseball. He built a professional team in Cincinnati that posted a 57-0 record, 64-0 including exhibitions, and 29-0 against professional teams.

The club followed that with a 67-6-1 record (27-6-1 against professional teams) in 1870, but after losing a game, fans stopped coming to see them, the club went broke, and the franchise collapsed.

The NA

Iver W. Adams capitalized on the collapse and brought Harry and his brother George to Boston, where he built a new Red Stockings Franchise. Wright’s new team dominated the fledgling National Association of Professional Base Ball Players League (the NA) so completely that it was often called Harry Wright’s League.

"(Wright) arranged all the games and (money) set up the travel schedule, negotiated hotel and railroad bills, negotiated player salaries, bought equipment, directed the groundskeeping, handled the media, and promoted Red Stockings games. It was this ingenuity on and off the field that he brought to Boston, bringing the city a championship-caliber professional team. Boston’s First Nine – the 1871-1875 Boston Red Stockings. page 2"

Wright took his team to Canada and convinced the Philadelphia Athletics to join the Red Stockings on the first overseas tour by professional baseball teams. The tour wasn’t the success Wright hoped for, and absent the two teams everyone wanted to watch, the NA’s precarious financial situation worsened.

Wright recognized the NA as a lost cause and switched his attention to the new league that included western clubs. The Red Stockings won the NA championship from 1872-1875 and finished their five seasons in the league with a 225 – 60 record.

The National League Rises

". . . from the ashes of the National Association emerged the Red Stockings’ model of success and the entrepreneurial genius of Chicago’s William Hulbert. John Thorn, “Our Game,” in Total Baseball, 6th ed. (New York: Total Sports, 1999), 5."

The Red Stockings lost many of their key players to the Chicago White Stockings (Cubs) open checkbook. Chicago won the league handily with Wright’s team in fourth, 15 games back.

Wright reversed that situation in 1877, bringing in future Hall of Famer Deacon White and adding pitcher Tommy Bond. White batted a league-leading .387/.405/.545/.950, good for a 193 OPS+.

Jim O’Rourke chipped in with a .362/.407/.445/.852 line and a 165 OPS+, future manager John Morrill added a .302/.319/.649 line and a102 OPS+, and Tommy Bond went 40-17 in 521 IP with a league-best 2.11 ERA, 135 ERA+. The Red Stockings won the Pennant with Chicago 15.5 games out in fifth place.