Montreal to Milwaukee

Jethroe earned the nickname of The Jet with Montreal because of his blazing speed on the bases. In 1949 the Dodgers timed him running a 5.9 60-yard dash, shaving two-tenths off the world record. The Dodgers set up a race between Jethroe and Olympic silver medalist Barney Ewell. Jethroe won going away.

In his 1.5 seasons in Montreal, he batted .325/.397/.505/.902 and delighted fans with his speed on the bases. in 1949, he drew the attention of New York sports writers by scoring from second standing up on an infield dribbler and set an International League single-season record for stolen bases with 89 steals. But with Duke Snider waiting for a call-up, the Dodgers had no room for him.

Finally Ready?

The Braves had a vacancy and made a headline-grabbing deal with Brooklyn, sending Al Epperly, Dee Phillips, Don Thompson, Clint Conatser, and cash worth between $1.2M and $2.5M in today’s dollars to Brooklyn for Jethroe and Bob Addis.

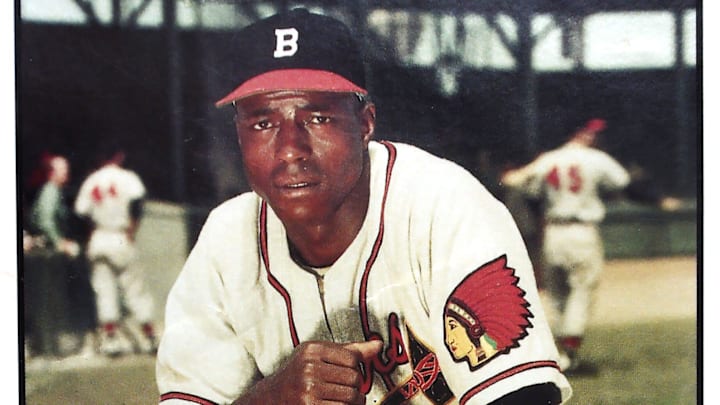

The following spring Sam Jethroe became the first African-American player in franchise history. Though he wasn’t a home run hitter before reaching the majors, he crushed 18 homers to go with 28 doubles and eight triples and ended the year with a .273/.338/.442/.780 line and a Major-League leading led the majors with 35 stolen bases.

The BBWAA made him an easy winner of the NL Rookie of the Year award, the first in Atlanta Braves Franchise history.

He repeated his success in 1952, once again slugging 18 homers and leading both leagues with 35 stolen bases in 40 attempts while batting .280/.356/.460/.816 with a 125 OPS+.

Off-season surgery meant Jethroe returned to the Braves without his usual strength. New Braves manager Charlie Grimm used a term that exposed his racial prejudice and didn’t hide his disdain for Sam. The club optioned him to Toledo in 1953 and traded him to Pittsburg after the season.

Michael Harris II - Atlanta Braves (2) pic.twitter.com/fav0tEGesp

— MLB HR Videos (@MLBHRVideos) June 15, 2022

Atlanta Braves Fans Love Mike as Boston Fans Loved Sam

Atlanta Fans expected something special when Money Mikey came to the plate, and he delivered excitement on both sides of the ball every game.

Boston fans loved The Jet from day one; every time the Jet got on base, they chanted go, go, go.

A fan who attended games and watched Jethroe explained what it was like in the ballpark in an email included in Jethroe’s SABR biography.

"“A wave of excitement rose from the stands when he stepped to the plate . . .he was our hometown answer to Jackie Robinson–a self-assured threat to steal one or more bases each time he reached first…Boos when he came to bat? Never. We just wanted to see Sammy run.”"

Jethroe was a quiet community activist before it was the popular thing to do. When he heard that the clubs planned to hold a Sam Jethroe day, “he asked instead that any money be put into a college scholarship for Negro youths.”

Similarly, Harris’ involvement with charities is well known, and his Catch 23 Foundation focuses on combating the stigma of mental illness, homelessness and promoting diversity and inclusion.

It sounds like these guys would’ve got along really well.