The Atlanta Braves’ worst-to-first season in 1991 echoes in fans’ minds today, but the 1914 Boston Braves did one better.

The history of the Atlanta Braves franchise is one of short-feasts and long-famines. The Bostons opened the 20th Century heading the wrong way: Kid Nichols bolted to the players league, the economy was weak, driving revenue down, and the roster aged quickly, sending the team to the bottom of the National League.

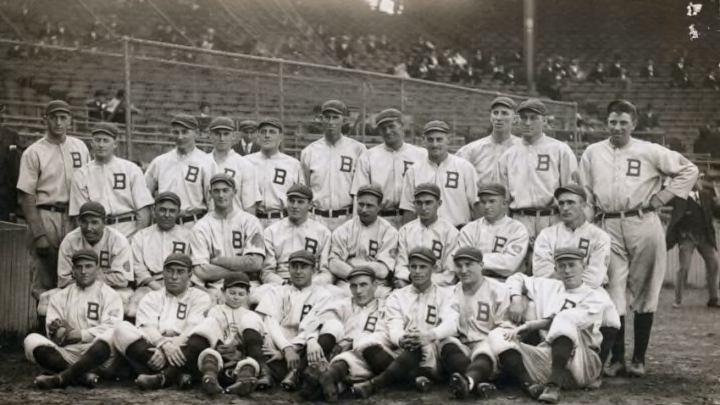

As I noted a few weeks ago, the team finished no higher than sixth place between 1903 through 1912. James Gaffney bought the club in 1911 and made Johnny Kling skipper, but Kling wasn’t able to prevent a fourth consecutive last-place finish, 52 games out of first. Gaffney fired Kling and hired George Stallings.

Stallings Early Career

George Tweedy Stallings’ Major League career consisted of four games without a hit in 1890, two games and one hit in 1897, and an appearance without coming to the plate in 1898; in all known games, he had 330 hits in 1508 PA.

He made good use of his time sitting on the bench and learned it well enough to manage his first of three clubs in 189. Stallings won his only minor league championship in 1895, taking the Nashville Seraphs to the Southern League title.

After a year with Detroit in 1896 in the American Association, the Phillies gave him his first Major League job as manager; they finished 10th of 12, started 1898 badly, and fired him.

Stallings returned to Detroit as minority owner and manager in 1899 and remained skipper through 1901, leading the Tigers to a 74-61 record and third-place finish in the American League’s inaugural season.

However, even a successful manager who’s also a minority owner of the team gets fired if he steps on the majority owner’s toes, particularly when the majority owner is American League president Ban Johnson.

The Comeback

Stallings returned to the minors for six years before deciding that having the League president fire you didn’t look good on his resumé, and retired to his Georgia plantation near Haddock, Georgia.

He resurrected a team that finished in seventh place with a 51- 103 – 1 record in 1908, leading them to a 74-77-2 fifth-place finish in 1909, and had a similar record near the end of 2010. However, Highlander first baseman Hal Chase, with the aid of Ban Johnson, convinced the owner to fire him and put Chase in charge.

A year after Chase lost his job, Gaffney hired him. Stallings later talked about his first impression of the Braves at the end of the 1912 season.

"(I) have never seen any club in the big leagues look quite so bad. The players were slow, ambitionless, careless and incapable . . . (and showed a) lack of spirit . . ."