My list of the Atlanta Braves Franchise top ten outfielders continues with a player who finished his career with 1500 + hits, a .300+ batting average, and an unbreakable record.

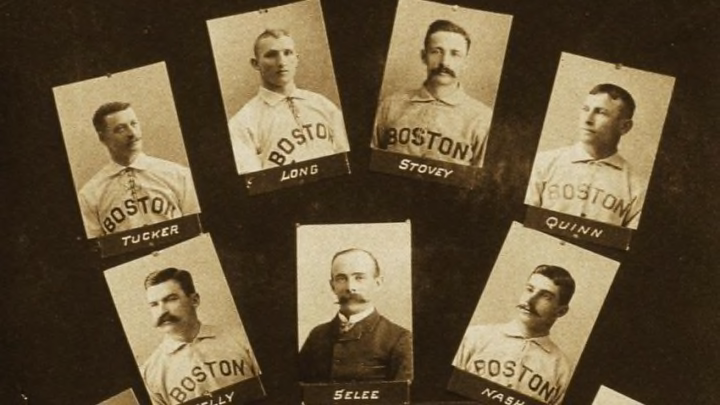

Part II of the series counting down the top ten outfielders in Atlanta Braves Franchise history led off will Billie Hamilton. Coming in at number six is the player Hamilton eventually replaced at the top of the Beaneater lineup: Hugh Duffy.

Throughout this post, I’ll reference Duffy’s SABR biography, news articles mentioned in those biographies that may not be available online any longer, and books that may no longer be widely available.

SABR is the definitive source for player information from the beginning of organized baseball, and most content is free to view. I encourage you to spend time reading and enjoying the stories there.

Hugh Duffy spent 1887 jumping from team to team in Massachusetts as each one folded, but his bat drew the attention of several Major League teams. When the season ended, Duffy negotiated a contract with the Chicago White Stockings (Cubs) that paid him more than many veterans.

“Shocked” is a fair description of White Stocking player/manager Cap Anson’s first look at his new, 24-year old outfielder. as described by Bill Lamb in The Glorious Beaneaters and recounted in his SABR Bio,

Duffy told of that first meeting often, and with a smile. Looking down at the short, fresh-faced kid, Anson bellowed, “What are you doing here? We already have a batboy.” Duffy had every reason to remember that day fondly, winning two batting titles and setting an all-time high for batting average in a single season.

Number six – Sir Hugh

| BA | OBP | SLG | OPS | AVG+ | OBP+ | SLG+ | wRC+ | wOBA | WAR | fWAR |

| .332 | .394 | .455 | .849 | 115 | 110 | 117 | 118 | .400 | 28.6 | 31.8 |

Sir Hugh joined the Beaneaters four seasons after that meeting with Anson, having batted .320/.384/.470/.853 while leading the ill-fated Players League in hits and runs in 1890, and leading the American Association in RBI and batting .336/.408/.453/.861 in 1891.

Duffy stood the same 5′-7″, 168 pounds as Atlanta Braves second baseman Ozzie Albies. Coincidentally another future Hall of Fame outfielder, Tommy McCarthy, arrived at the same time as Duffy; he was also 5′-7″, 168 pounds.

Like Albies and his buddy Ronald Acuna Jr. with Atlanta, Duffy and McCarthy injected fire and excitement into the Beaneaters lineup. Boston press soon dubbed the pair “The Heavenly Twins.”

The pair didn’t look the same, but they played the game the same way as Albies and Acuna – aggressively. Both had a high baseball IQ and recognized the problem they could cause opposing teams. Hitting at the top of the Beaneaters order, Duffy and McCarthy changed the way the game was played in the early 1890s.