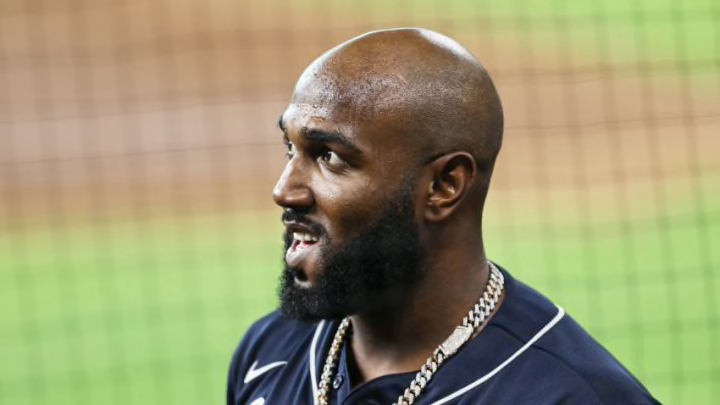

After the arrest of the Atlanta Braves high-profile, high-dollar dollar free agent, fans want the club to take action, but the team has few viable options.

We’ve all read about the arrest of Atlanta Braves outfielder Marcell Ozuna, and Alan wrote in general about the club’s options. However, fans continue to ask why the team doesn’t take action. The answer lies in the Joint Domestic Violence Policy collectively bargained in 2015, which was expanded and incorporated into the 2017-2021 Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA).

The goal here isn’t to discuss what should or shouldn’t happen to the Atlanta Braves outfielder but to explain the team’s options under the CBA.

The only reference to domestic violence in the 2012-2016 CBA came in Attachment 27—Joint Treatment Program for Alcohol-Related and Off-Field Violent Conduct; a letter from MLB Executive VP Robert Manfred, to then MLBPA Executive Director Michael Weiner, confirming that the union and MLB had agreed to establish a “Joint Treatment Program to deal with certain alcohol-related conduct and off-field violent conduct.”

If a player was arrested for an alcohol-related event, appeared intoxicated on the job, medical staff suspected an alcohol problem, or the player was arrested, the incident was referred to the Treatment Board.

The Treatment Board evaluated the player to determine if he would “benefit from a treatment program and, if so, the type of treatment program that would be most effective

for the Player involved.” However, the player’s participation was voluntary; failure to attend could not result in disciplinary action.

If the Ozuna incident had happened in 2013, the league could have suspended him until the legal system took its course or placed him on the ineligible list if incarcerated; aside from that, the only option for the league was asking the player to attend a treatment program, which he could have refused to attend without penalty.

Unsurprisingly, that program wasn’t much of a determent. Once he became commissioner, Manfred and worked with MLBPA’s new executive director Tony Clark to expand the policy to include minor league players and add more teeth.