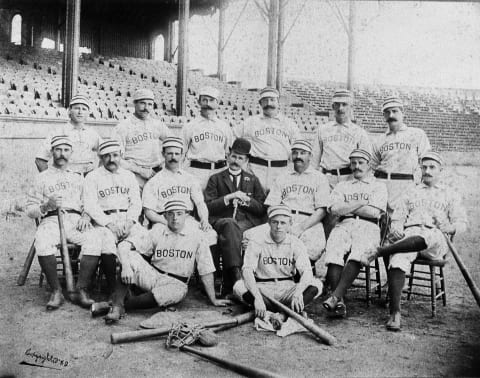

Atlanta Braves Franchise best catchers: King Kelly

Our parade of Atlanta Braves franchise greats continues with a look at those handling great Braves pitching in the most physically demanding position on the field, catchers.

Selecting the noteworthy Atlanta Braves franchise catchers proved more difficult than I imagined. I thought I had it narrowed down to five, but by the time I finished digging into the details of each player’s career, I cheated and settled on six. But it’s my list so I’m allowed.

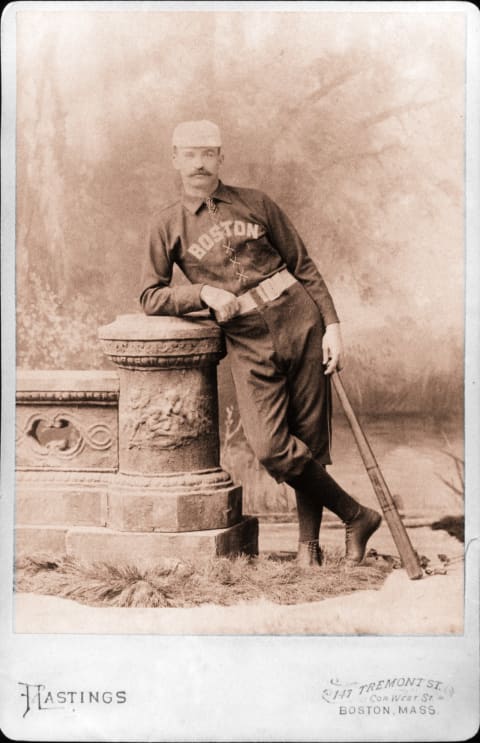

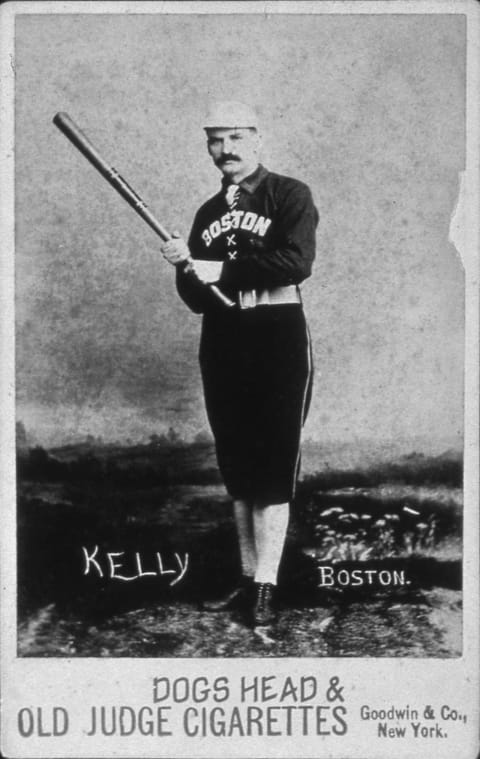

Michael J “King” Kelly, was a larger-than-life star before mass communications existed. His SABR bio opens with a perfect description.

. . . the first ballplayer to “author” an autobiography, the first to have a hit song written about him, and the first to have a successful acting career outside the game. A handsome man with a full mustache and a head of red hair, Kelly through his fame helped change professional baseball from a pleasant diversion into America’s most popular sport.

Orphaned before he graduated from grade school, Kelly didn’t hang his head; instead, he studied and worked at a coal factory carrying buckets of coal to the roof. After work, he played sports and acted in amateur plays. At 15-years old, the Paterson (New Jersey) Keystones recruited him, and by 18, he was their starting catcher.

In 1877 he moved to a team in New York then signed a contract to play in Ohio, but the team disbanded after the season. The Cincinnati Red Stockings liked him enough to offer him a contract, and, at 20-years old, he became one of their ten reserved players.

By 1879 when he hit .348, Kelly was a star; he was also baseball smart. You may remember Atlanta Braves new shortstop Yunel Escobar pilfering second while the pitcher tied his shoe; Kelly did a lot better than that:

Kelly stroked a double to left. After he rounded second, the ball came in to Chicago second baseman Joe Quest, who thought he tagged Kelly out. The umpire called Kelly safe, which led to a fervent argument . . . Kelly, realizing that no one had called time, jumped up and came home to score. . .

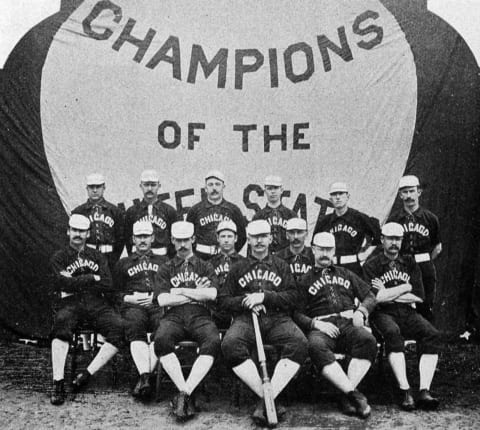

When the Red Stockings folded, he traveled with Cap Anson, who eventually signed him for the Chicago White Stockings; Anson and Kelly both have plaques at Cooperstown.

Although he played only three seasons for Boston, it’s impossible to leave a player with that resume off of the list – okay, it’s possible, but why do it? Kelly was known for drinking, using the rules to his advantage, and being a humble man. He was also the catcher on a Beaneaters NL Championship team.

Number six: All hail the King

The Atlanta Braves Franchise first – and only– celebrity/superstar off the field, catcher arrived in Boston for the 1888 season.

Kelly became a star in his seven seasons with Chicago White Stockings (Cubs), leading the NL in doubles twice, runs scored three times, and winning two batting titles; batting .354/.414/.524/.938 in 1884 and .399/.483*.534/1.018 in 1886. The 1886 season elevated Kelly to the top-tier of stars in the NL, and fans began calling him King Kelly or “the only Kelly.”

Like most players of that era, Kelly played multiple positions – outfield, third base, and shortstop – as well as catching and doing a little relief pitching as well.

More from Braves History

- Atlanta Braves History: How the Red Stockings became the Braves

- Atlanta Braves 2022 Season Review: Jackson Stephens

- Travis d’Arnaud is an unsung hero of the Atlanta Braves

- Eight of the craziest injuries in Atlanta Braves franchise history

- Why the Atlanta Braves’ Dale Murphy shouldn’t be in the Hall of Fame

Catcher defense wasn’t a priority in that era, which was a good thing for Kelly, because he wasn’t a good defender behind the plate. Teams wanted Kelly for his inventiveness and bat; he’d averaged 29 doubles a year from 1881 through 1886 and was sixth in league with 13 homers in 1884.

Kelly liked Chicago and would have gladly agreed to stay except owner Al Spalding wanted him to curtail his favorite sport; drinking. Spalding even withheld pay that the players could get back by playing sober and had players followed to find out who was drinking. After the Cubs failed to beat St Louis – a portent of the team’s future – Spalding decided to get new blood by trading away older stars.

The Beaneaters needed both his production and the fans they knew he’d bring to the games, so they opened their checkbook and Chicago $10,000 ($275,590 in today’s dollars) for Kelly. To keep Kelly happy, Boston paid him $5,000 a year circumventing the league’s salary cap of $2,000 by paying him that plus an additional $3000 for ‘using his picture in advertising’.

Boston belongs to King Kelly

| G | R | RBI | SB | AVG | OBP | SLG |

| 348 | 372 | 258 | 238 | .311 | .379 | .471 |

| HR | ISO+ | wOBA | wRC+ | AVG+ | OBP+ | SLG+ |

| 26 | 138 | .395 | 133 | 110 | 112 | 118 |

Kelly was the stereotypical Irishman, smiling, gregarious, as well as being a good player. The Beaneaters hoped the affable Irishman would woo Boston’s large Irish population and increase attendance at their games. They needn’t have worried, Kelly’s arrival was an event in Boston, as SABR’s Marty Appel wrote.

the arrival of Mike Kelly in 1887 seemed something like a homecoming — a hero’s return. . . playing everyday at the South End Grounds on Walpole Street, he would be huge (draw) . . . . . . kids knew his arrival schedule (and waited) for a chance to see Kelly in person. (He was hard to miss, often toting a pet monkey on his shoulder.). .

Peter Gordon credits Kelly with making the autograph popular, kids followed him down the street away from the ballpark, and Kelly was always ready to sign for his fans.

Kelly may not have been the first baseball player fans followed for an autograph, but as the most famous he can certainly be given credit for popularizing the practice.

Kelly earned his money from day one, selling out games in his first starts. On the season, he stole 84 bases while batting 322/.393/.488 as Boston took the NL title.

Kelly batted .318/.368/.480/.848 in 1888, but the Beaneaters faded down the stretch. In 1889 he slumped to .294/.376/.448/.824 but led the league in doubles as Boston lost on the last day of the season and finished second.

Kelly’s stardom brought him extra cash from endorsements that included a “Slide, Kelly, Slide” sled. Kelly shoe polish and pictures of his sliding headfirst into second base were prominent in bars across the city

The 1889 season also saw vaudeville star Maggie Cline sing “Slide, Kelly Slide,” referring to Kelly’s habit of sliding headfirst into second base.

Atlanta Braves Franchise’s King abdicates, then returns

Salary disputes between the players and the league led to the formation of the Player’s League, and Kelly left the Beaneaters in support of the players but remained in Boston to play for – and manage – the Boston Reds, along with fellow Beaneaters Dan Brouthers, Tome Brown, Old Hoss Radbourn and Hardy Richardson.

His stay with the Reds lasted one season, then he formed Kelly’s Killers in the American Association and became player/manager. The Killers lasted until the season ended in August. Kelly released himself and signed back with the Boston Reds, only to jump back to the Beaneaters a week later.

The Beaneaters were now a shell of their championship selves, and Kelly’s hard-living ways made him a shell of his former self. He played with the Beaneaters through the 1892 season, signed with the Giants in May of 1893, but played just 20 games for New York.

Epilogue

After spending the winter booking vaudeville acts, Kelly played some minor league ball in 1894 and hit well at that level, but knew that was the end of his baseball career. He performed in vaudeville, trying to earn money to support his wife and one-year-old child. Kelly spent money as fast as he made it and was soon broke once he stopped playing.

In November 1894, he traveled by boat to Boston and became ill, reportedly because he gave his coat to another older passenger. On Monday later he was diagnosed with pneumonia.

(Former Beaneater team doctor) Galvin moved Kelly to Emergency Hospital. It was reported that when Kelly came to the hospital the stretcher carrying him slipped to the floor, and he said, “This is my last slide.”

His illness was headline news in Boston, and the doctors called for his wife to come to Boston. On Thursday afternoon, Kelly received last rites; at 9:55 that night, he died of pneumonia, Kelly was 36-years old.

Gordon (linked above) summed up his life.

Kelly did as much as any other player to popularize professional baseball in . . .. His popularity transcended the game . . . It was said that half the rules in the baseball (changed) to keep Kelly from (using) loopholes. He played the game with gusto . . .his teams won eight championships in 16 years . . .

That’s a wrap

Kelly was the first real superstar draw in Boston sports and a forgotten, but historical figure who changed the game forever; not many players do that.

His time with the Atlanta Braves Franchise Beaneaters was a short, exciting ride that ended too quickly. No one knows – or at least I couldn’t find out – if any of his family knew of his selection for the Hall of Fame in 1945 (as a right fielder, don’t get me started) or the induction the following year. That, my friends, is a shame.

Next. Hank's the best. dark

Next up, the first Hammerin’ Hank.