Atlanta Braves history: Johnny Antonelli the first Bonus Baby

Atlanta Braves history has its share of can’t miss prospects, who don’t pan out. Some lack talent, while others were victims of unintended consequences.

What follows is a baseball epitaph for a man who made history for the Atlanta Braves franchise and MLB.

On June 29, 1948, the Atlanta Braves franchise signed the first bonus baby in baseball history, 18-year old lefty Johnny Antonelli. He was projected as the top of a rotation starter he finally became, but not for the Braves.

Stop me if you’ve heard this before. In 1947 baseball decided that in an attempt to improve competitive balance, it needed rules to prevent rich teams like the Yankees, Dodgers, Red Sox, and Cardinals from signing every good prospect and using the reserve clause hide them in the minors forever. They settled on something called the bonus rule.

The original bonus rule worked in the same way the Rule 5 draft does today. Players receiving a large signing bonus had to stay on the Major League roster for a full season. The rule lasted three seasons, but rose from the ashes in 1952, this time with a two-year requirement.

On page 125 of the Dickson Baseball Dictionary, the author defines and quantifies the result of the Bonus Baby rules.

“Bonus Baby: A free-agent player signed under the bonus rule of 1953-1957. Such players were usually 18 or 19 years old, so full of talent and promise that they overshadowed their high school or college teammates and had professional teams scrambling to sign them; however, many bonus babies had failed careers as they were not ready for baseball at the major-league level and their talent rusted in idleness on the bench”

Johnny be good

As discussed in Antonelli’s Sabre bio, Johnny’s father, Gus Antonelli, immigrated to America in 1913 and worked hard to give his family a better life. He recognized his son’s baseball talent early and began grooming him for professional ball.

(Unless otherwise specified, all quotes come from his bio linked above. I tried to get to their source material listed in the footnotes, but much of it isn’t available online.)

The young lefty threw three no-hitters before his senior year in high school, impressing Carl Hubble so much that he said Antonelli had the best all-around stuff he’d ever seen.

After graduation, Gus rented a minor league ballpark in Rochester and invited scouts to watch Johnny pitch against a semi-pro team. He threw a complete-game no-hitter striking out 17, and the battle of checkbooks began. Braves scout Jeff Jones told team president, Lou Perini, the kid was good.

“He’s by far the best big-league prospect I’ve ever seen. . . He has the poise of a major league pitcher right now and has a curve and fastball to back it up . . . if I had to pay out the money myself, I wouldn’t hesitate . . .

The Baseball Almanac show Antonelli received a $65,000 bonus, about $696,000 today, from the Boston Braves making him the first player in baseball history – and the only player under the first version of the rule – to carry the Bonus Baby tag,

Left-hander MacKenzie Gore drew similar comments before the 2017 draft. Baseball America (behind a paywall, so I’m paraphrasing and not allowed to link), suggested Gore topped the list of high schoolers, possessed poise beyond his years, had great stuff, and pounded the zone.

Imagine the Atlanta Braves bypassing Kyle Wright and signing Gore for the $6.7M the Padres gave him, knowing he had to take a 25-man roster spot in 2018 and make more money than everyone except Freddie Freeman, Nick Markakis, and Julio Teheran. Would the players like that?

No, and Antonelli’s teammates didn’t either.

Being a Brave

Antonelli took a lot of heat in 1948. Like the 2018 Atlanta Braves, the Boston Braves were locked in a tight pennant race, and the rookie making three times the salary of Johnny Sain appeared in four games and threw four innings. His primary task that season was tossing batting practice before each game.

The 1949 season saw Antonelli given more starts and producing better results. On May 1, he flashed the stuff that earned him the big signing bonus.

After Warren Spahn beat the Giants in game one of the double-header, Antonelli gave up an unearned run in the top of the first, then threw seven shutout innings to get the win and help the Braves sweep the twin-bill. On June 12, he threw a four-hit shutout against the Cubs for his second win of the season.

More from Tomahawk Take

- Atlanta Braves 2012 Prospect Review: Joey Terdoslavich

- Braves News: Braves sign Fuentes, Andruw’s HOF candidacy, more

- The Weakest Braves Homers Since 2015

- Atlanta Braves Sign Joshua Fuentes to Minor League Deal

- Braves News: New Year’s Eve comes with several questions about the 2023 Braves

Antonelli finished the season with a 3-7 record in ten starts and 12 relief appearances, throwing 96 innings with a 3.56 ERA and 107 ERA+. In 1950, the Braves weren’t as good, and neither was Antonelli. He finished the 1950 season with a 5.93 ERA in 57 innings over 20 appearances, but a 3.24 FIP suggests he pitched a lot better than his record.

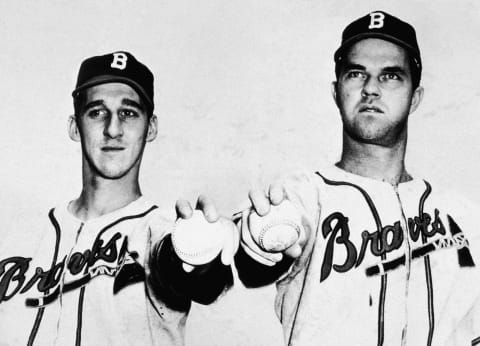

After two years in the Army, Johnny Antonelli returned to the now Milwaukee Braves and looked remarkably like the guy they thought they’d signed in 1948. He made 26 starts, threw 175 1/3 innings, including eleven complete games and two shutouts while pitching to a 3.18 ERA, 3.44 FIP, and 124 ERA+.

Always willing to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, the Braves traded him to the Giants the following December.

Oops, bad deal

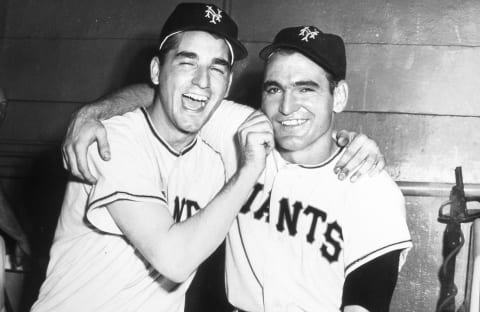

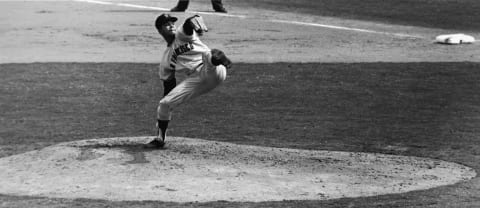

In 1954, Antonelli – now 24-years old, became the Giants’ best starting pitcher. He appeared in 39 games, threw 258 1/3 innings, including 36 starts, won 21, lost 7, and notched two saves. The lefty led the leagues with six shutouts, a 2.30 ERA, and 178 ERA+, earning him his first of five All-Star nods that July and a third place finish third in NL MVP voting.

Giants pitching faltered in late August, but Antonelli refused to lose. His Sabre bio linked earlier describes his work.

. . . Behind his clutch hurling and offensive support from the likes of Willie Mays, Monte Irvin, and Alvin Dark, the Giants advanced to the World Series against the Cleveland Indians.

He came up big for the Giants World Series sweep on the Indians, winning game two with an eight-hit, one run, complete game, then coming back in game four and the 1 2/3 innings of no-hit shutout ball to earn the save. He finished the series with a 0.84 ERA and 12 strikeouts in 10 1/3 IP.

Antonelli was a very good – at times great – pitcher in his seven years with the Giants, earning another top-20 MVP finish in 1956, and leading the league in shutouts again, with four in 1959.

| ERA | G | GS | CG | SHO | SV | IP | ERA+ | FIP | |

| 3.13 | 280 | 219 | 86 | 21 | 19 | 1600 | 124 | 3.58 |

He could hit a bit too.

| H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | BA | OBP | SLG | OPS | SF |

| 101 | 8 | 3 | 15 | 54 | .180 | .212 | .286 | .497 | 25 |

The Braves received catcher Sam Calderone and Bobby Thompson in the trade. Calderone made 34 plate appearances in 1954 spent the rest of his career in the minors. Thompson batted .242/.307/.400/.706 with a 92 OPS+ over his three-plus seasons with the Braves.

The Braves also sent Don Liddle – two-plus years for the Giants 274 1/3 IP 3.64 ERA – catcher Ebba St. Claire – a 1954 season that duplicated Calderone’s, minor league infielder Billy Klaus, and $50,000 to the Giants in that deal. Good job, Mr. Quinn.

It’s windy in San Francisco

Antonelli didn’t like San Francisco, and he wasn’t alone. To make matters worse, the Giants moved him to the bullpen.

His dissatisfaction with that west coast city was a sentiment that had been shared by his teammates in the Bay Area, and the tension in the clubhouse was compounded by the fact that Johnny had been moved to the bullpen for the first time since his rookie year.

Fans blamed him for the Giants’ collapse, even though Jack Sanford had similar numbers, and only two of the five regular starters had winning records. He complained about the wind at Seal Stadium, but fans focused on his complaints about San Francisco, not his statistics, which were as good as Sanford’s on a team that finished 79-77, fifth in the league.

The Giants played at Seals Stadium. . .fondly remembered by everybody but Johnny Antonelli, the San Francisco pitcher who disliked the place, said so and was roundly booed, a New Yorker on the wrong coast.

Antonelli never adapted to the West Coast lifestyle. The Giants traded him to the Indians, who, in turn, traded him to the Braves. After the season, the Braves sold his contract to the Mets, and Antonelli retired.

I quit baseball because I didn’t like traveling, Johnny said in 2007. Not for any other reason. I had no injuries or anything. I’d had my fill of traveling. I had a business to fall back on or else I would have played longer, I’m sure.

Lessons unlearned

Owners are still trying to create the nonexistent level playing field of competitive balance, with only marginal success. Rich teams will always have an advantage, and while some measures have helped others have not.

Forced to rush him into the majors, the Boston Braves stunted Antonelli’s growth as a pitcher, a mistake the Atlanta Braves, thankfully, refuse so far, to make.

In 1953, Antonelli had enough experience to justify a place on the Braves 25-man roster and demonstrated his readiness over a winning season. The Braves’ front office and leadership – Charlie Grimm again – traded him in what has to rank among the worst deals ever made.

That’s a wrap

Johnny Antonelli came to the big leagues fresh out of high school at 18-years old, at a time in history when teenagers weren’t nearly as worldly as they are now. He never liked being outside of New England, a perpetually homesick young man, lost in an unfamiliar place with an uncomfortable atmosphere.

Fans forget players are people with private lives and feelings. When Antonelli struggled, fans responded by booing him. The unwarranted barrage of negative noise added insult to injury. At 30 years old, Antonelli had enough of traveling, booing, and life outside of New England. He wanted to go home and did.

Next. Slipsees. dark

On Friday, February 28, 2020, Johnny Antonelli died. He was 89-years old. Rest well, Johnny, you’re home.